More Information

Submitted: November 26, 2025 | Accepted: December 11, 2025 | Published: December 12, 2025

Citation: Jerkic A, Karavdic K, Muhovic S, Kulo A,Salibasic M, Jonuzi A, Firdus A. Clinical Characteristics of Pediatric Patients with Gallbladder Disease Surgically Treated at the Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinical Center of the University of Sarajevo, over a 15-year Period. Arch Surg Clin Res. 2025; 9(2): 045-057. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ascr.1001092.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ascr.1001092

Copyright license: © 2025 Jerkic A, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Gallbladder; Cholelithiasis; Cholecystitis; Cholecystectomy; Spherocytosis; Pediatric obesity

Clinical Characteristics of Pediatric Patients with Gallbladder Disease Surgically Treated at the Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinical Center of the University of Sarajevo, over a 15-year Period

A Jerkic1, Karavdic K2*, S Muhovic3, A Kulo3, M Salibasic3, A Jonuzi2 and A Firdus2

1Medical Faculty, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

2Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinic Center of the University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

3Clinic for Abdominal Surgery, Clinic Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

*Corresponding author: Kenan Karavdic, Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinic Center of the University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: Acquired gallbladder diseases in the pediatric population, although rare, are becoming increasingly recognized in clinical practice. The growing number of pediatric cholecystectomies may be attributed to improved diagnostic modalities as well as to shifts in etiological patterns, including the rising prevalence of obesity and metabolic disorders among children and adolescents.

Aim: The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical and laboratory presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment of pediatric patients who underwent cholecystectomy at the Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, University of Sarajevo, between 2010 and 2024.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective descriptive study included 41 patients who underwent cholecystectomy. Medical records were reviewed to collect data on clinical presentation and disease course. Based on the median age within the sample, patients were stratified into two groups: children under 14 years and those aged 14 years or older.

Results: 41 patients were included in the study, comprising 25 (61%) girls and 16 (39%) boys. Between 2010 and 2024, the number of cholecystectomized patients increased by 11.2% annually (p = 0.0057). The median patient age was 14 years. The mean BMI was 23.2 ± 4.66 kg/m²; 51.22% of patients were overweight, and 4.88% were obese. The most frequent diagnosis was chronic calculous cholecystitis, confirmed in 36 patients (87.8%). Spherocytosis was documented in 7 patients (17.7%). Multiple gallstones were present in 29 patients (74.36%), and the majority of sonographically detected gallstones (31 patients, 79.49%) were smaller than 5 mm. Smaller stones tended to occur more frequently (p = –0.53, p < 0.001). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 37 patients (90.24%). The average length of hospitalization decreased by approximately 11.9% annually (p < 0.01). Gallstone color was reported in the histopathological findings of 16 patients (41.03%), of which 9 were cholesterol (56.25%) and 7 pigment stones (43.75%). With each additional year of age, the risk of undergoing cholecystectomy increased by 21.5% (p < 0.01). Pigment stones were significantly more frequent in children under 14, while cholesterol stones predominated in those aged 14 years or older (p = 0.0406).

Conclusion: The incidence of gallbladder disease is continuously increasing in the pediatric population. Obesity and older pediatric age are significant risk factors for cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy remains the standard treatment approach.

Cholelithiasis (lat. cholelithiasis) refers to the presence of one or more calculi in the gallbladder or bile ducts. The term cholecystitis (lat. cholecystitis) refers to inflammation of the gallbladder. Acute cholecystitis predominantly occurs as a complication of cholelithiasis and mainly develops in patients with a history of symptomatic gallbladder calculi. Although this is generally a disease of adults, risk factors such as adolescent obesity, neonatal short bowel syndrome, total parenteral nutrition, and some hereditary conditions such as spherocytosis make it a significant pathological condition in the pediatric population [1].

Most studies of cholelithiasis in the pediatric population show a bimodal distribution with a smaller increase in the infant period and a gradual increase in frequency from early adolescence [2]. Cholelithiasis in the pediatric population was considered a complication of prematurity and hemolytic anemia in the past, but in the last three decades, the incidence of its diagnosis and surgical treatment has increased significantly. This can be attributed in part to improved diagnostic modalities (primarily ultrasound), but also to altered pathology, which now includes new comorbidities such as pediatric obesity and associated risk factors [3]. It is generally considered that the prevalence of cholelithiasis in children is between 0.13% and 1.9%, but in the last 20 years or so, a significant increase in the number of cases of nonhemolytic cholelithiasis has been recorded, from 1.9% to even 4%, with obesity as the main cause [4]. Infants under the age of 6 months account for 10%, children between the ages of 6 months and 10 years account for 21%, and adolescents aged 11 to 21 years account for 69% of all cases of pediatric cholelithiasis. The distribution before puberty is the same for both sexes, while after puberty, it assumes the characteristics of the adult population with a female-to-male ratio of 4:1. 4% of all cholecystectomies occur in patients younger than 20 years. (14) Hispanic ethnicity has been identified as an independent predisposing factor for the development of pediatric cholelithiasis [5].

In the last three decades, a significant change has been recorded in the epidemiological pattern of gallbladder disease in the pediatric population, with an increase in the incidence of the disease and associated complications requiring surgical treatment. Although gallbladder disease was primarily considered a complication of prematurity and hemolytic anemia in the past, modern data indicate an increasing prevalence of non-hemolytic causes, with metabolic disorders, such as adolescent obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, dominating. A retrospective analysis of the clinical spectrum of these diseases, their etiological factors, laboratory findings, surgical techniques, and postoperative outcomes would significantly contribute to better diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic stratification of patients.

An observational retrospective descriptive study was conducted, covering the period from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2024. Data on patients included in the study were taken from the medical histories of the Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinical Center, University of Sarajevo. The study included 41 patients who underwent cholecystectomy during the specified time period and who met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: Patients under 18 years of age, patients with a primary diagnosis of gallbladder disease (cholelithiasis, cholecystitis), and patients whose treatment included cholecystectomy surgery.

Exclusion criteria: patients older than 18 years, patients with a primary diagnosis of diseases of the biliary tree, patients treated only conservatively, šatients with incomplete medical documentation.

In order to understand the clinical characteristics of gallbladder disease in pediatric patients, anamnestic data, physical examination findings, laboratory findings, results of diagnostic procedures, basic information about surgery, and postoperative antibiotic treatment were taken and analyzed from the disease history. Basic patient data included age and sex, height and weight, date of admission and discharge (length of hospitalization), anamnestic data on the localization of pain and other complaints related to the diseases. Data on the present comorbidities (with an emphasis on one that is considered a predisposing condition for the development of gallbladder disease) were taken from the patient's personal history, and the presence of gallbladder disease in the patient's family was taken from the family history. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from the patient's height and weight, which was standardized for comparison in pediatric patients and presented as a Z-score and percentile using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) based on reference values for children and adolescents.

Laboratory findings relevant to gallbladder disease were taken from the laboratory findings, such as parameters of hemolysis, inflammation, liver function, hepatobiliary tract function, secondary abnormal pancreatic activity, including: erythrocyte count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, sedimentation rate, leukocyte and platelet count, ALT, direct blood concentration, CRP, and indirect. LDH, alkaline phosphatase, amylase, and lipase, respectively. Pediatric patients are subject to special reference intervals for most laboratory findings, based on gender and age, and deviations from physiological values were standardized according to the Canadian Laboratory Initiative on Pediatric Reference Intervals (CALIPER) guidelines (100).

The analyzed diagnostic procedures included ultrasonography results and histopathological examination findings. Data on the presence, number, and location of gallstones, gallbladder wall thickening, and bile duct dilation were taken from ultrasonographic findings and from pathohistological examinations. In addition to the above, data on the color of gallstones, congenital anomalies of the gallbladder, and the presence of mucosal metaplasia were also derived. Data on the method of cholecystectomy (laparoscopic or open approach) and possible conversions were derived from the surgical lists. The postoperative antibiotic regimen and duration of its application were recorded, as well as the postoperative day of drain removal.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo), the Declaration of Helsinki on Patients' Rights in Biomedical Research and its latest revision, as well as national laws on patients' rights (Law on the Rights, Obligations and Responsibilities of Patients in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Law on the Protection of Personal Data, Rulebook on Regulations and Records in the Healthcare Sector of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina). The Organizational Unit for Science, Teaching and Clinical Research of the Clinical Center of the University of Sarajevo granted consent to conduct the research and access to the medical documentation of the Clinic for Pediatric Surgery of the KCUS (Act No. 16-33-6-13677, issued on April 15, 2025, in Sarajevo). In order to identify possible differences in clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and postoperative outcomes in relation to age, the subjects were stratified into two groups based on the median age value, which in the analyzed sample was 14 years. Descriptive statistical analysis included the median, 1st and 3rd quartiles (Q1, Q3), interquartile range (IQR), minimum and maximum values for non-parametric distributed variables, arithmetic mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables, and percentage of representation. The data are presented in tables and graphs.

The normality of the distribution of quantitative variations is due to the sample size tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Based on the test results, the data were further analyzed by appropriate parametric and non-parametric statistical methods. The homogeneity of variances between groups was checked by Levene's test. In case of violated homogeneity of variances, Welch's t-test was applied. For the comparison of two groups in which the distribution deviates from normal, the Mann-Whitney test was used. Categorical variables whose distribution deviated from normal were tested by Fisher's exact test, in accordance with the large sample. For the comparison of the values of a continuous variable between multiple independent categories of groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, considering the deviation from the parametric distribution. Poisson regression analysis was used to examine the association between the dependent continuous variable and independent predictors, while ordinal logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between the categorical dependent variable and multiple predictors. In case of non-normality of the residual distribution and log-linear relationship between variables, a log-linear regression model was applied. Statistical significance was defined for p - values <0.05. For multiple testing within the same group, the Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to control for false discovery.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the R software package version 4.5.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

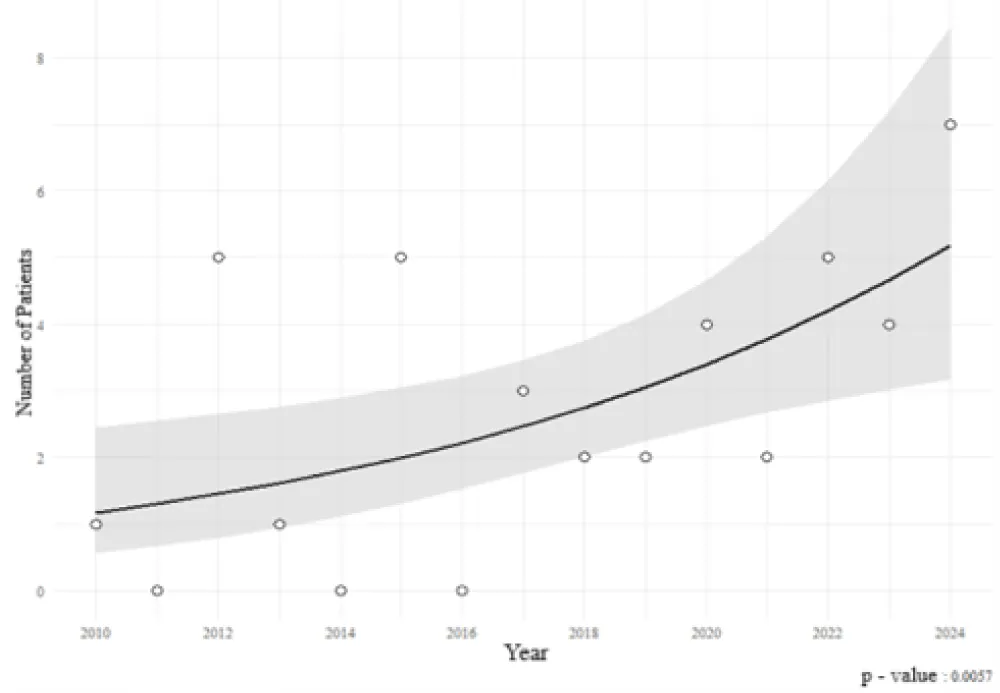

A total of 41 pediatric patients who underwent cholecystectomy were included in the study. Among them, 25 (61%) were female, and 16 (39%) were male. Between 2010 and 2024, the number of pediatric cholecystectomies increased by 11.2% annually (95% CI: 3.1% to 19.9%), a statistically significant trend (p = 0.0057) illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Trend in Annual Number of Cholecystectomies in the Pediatric Population (2010–2024) - Results of Poisson Regression Analysis.

The age distribution of patients deviated significantly from normality (p = 0.0001), with a median age of 14 years. The youngest patient was one year old, and the oldest was 17 years (IQR = 4). Median age was identical in both sexes (14 years), with a wider range observed in boys (1–17 years, IQR = 6.25) compared to girls (8–17 years, IQR = 4). No statistically significant age difference was found between sexes (p = 0.8929).

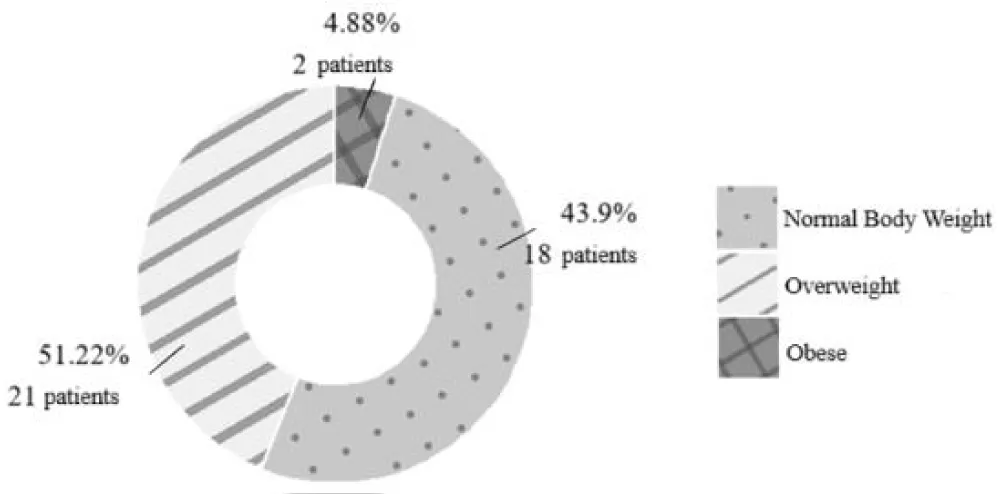

The mean BMI of patients was 23.2 ± 4.66 kg/m², with a mean BMI Z-score of 0.9 ± 0.77, corresponding to the 82nd percentile. BMI distribution followed a normal pattern (p = 0.5021). Based on BMI Z-scores, 51.22% of patients were classified as overweight and 4.88% as obese (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Body Weight Among Patients According to the Pediatric BMI Z-Score.

A weak positive correlation was observed between age and BMI Z-score in both females (p = 0.22, p = 0.2826) and males (p = 0.18, p = 0.5146), although neither reached statistical significance.

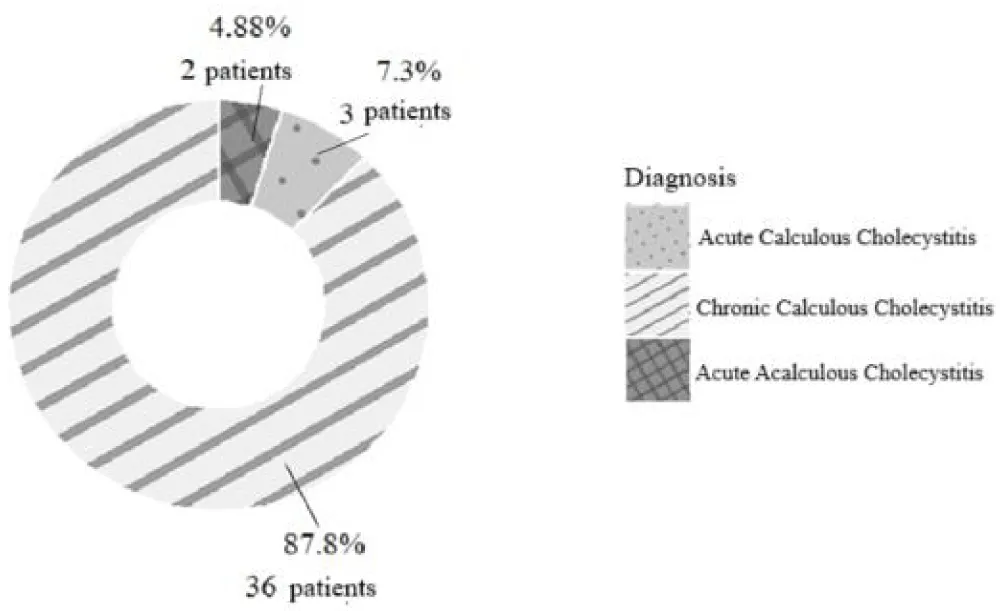

The most frequent preoperative diagnosis was calculous cholecystitis observed in 39 patients (95.1%), with chronic calculous cholecystitis confirmed in 36 cases (87.8%) and acute calculous cholecystitis in 3 cases (7.3%). Two patients (4.88%) were diagnosed with acute acalculous cholecystitis (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Preoperative Distribution of Clinical Diagnoses Among Patients.

Etiologic factors known to cause cholelithiasis were identified in 10 patients (25%), with hereditary spherocytosis being the most prevalent (17.1%) (Table 1). Patients with spherocytosis were significantly younger at the time of surgery (median age 9 vs. 14 years; p = 0.0064).

| Table1: Prevalence of known etiological factors in the development of gallstones in children | ||

| Condition | N | % |

| Hereditary Spherocytosis | 7 | 17.07 |

| Chronic Liver Disease | 2 | 4.88 |

| Kidney Transplantation | 1 | 2.44 |

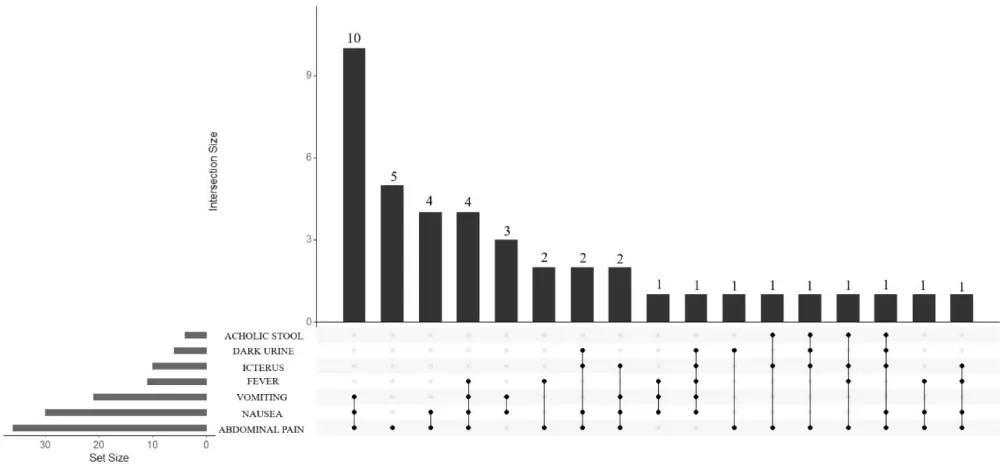

The most common symptom was abdominal pain, present in 36 cases (87.8%), followed by nausea in 30 patients (73.2%), vomiting in 21 (51.2%), and fever in 11 cases (26.8%). The most frequent symptom combination was abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting observed in 10 cases (24.4%).

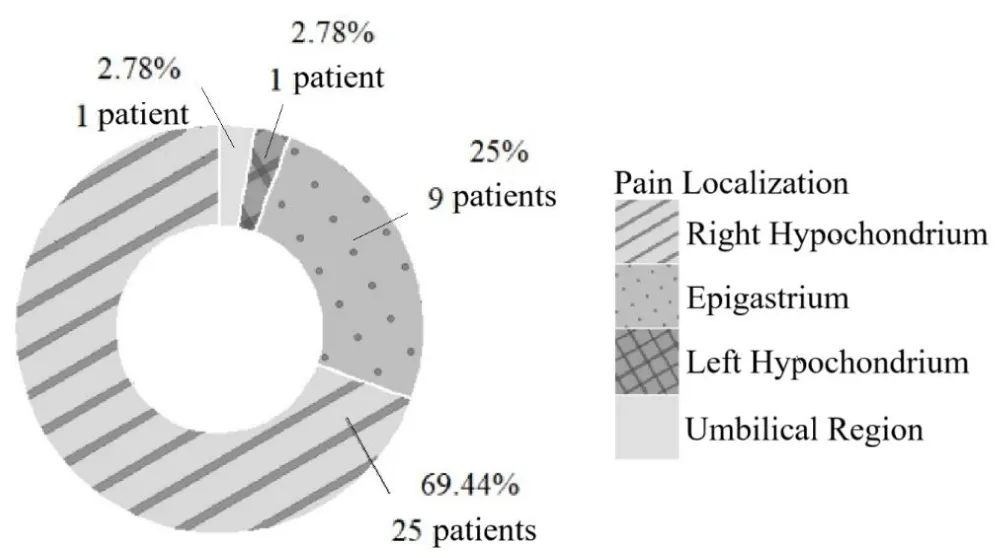

Pain localization was most frequently reported in the right hypochondrium, in 25 cases (69.4%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Prevalence of Clinical Symptoms and Signs in Children With Gallbladder Disease.

Figure 5: Prevalence of Abdominal Pain Localization in Children with Gallbladder Disease.

Descriptive statistics of preoperative laboratory values (Table 2) indicated that hemoglobin, hematocrit, ALP, and platelet count followed a normal distribution (p > 0.05), while other parameters did not. Elevated liver enzymes were frequently observed: AST (63.4%), ALT (78.1%), γGT (85.4%), along with raised CRP (60.98%) and ESR (87.8%), suggesting an inflammatory and hepatobiliary dysfunction profile. Hyperbilirubinemia was found in 78.05% of patients, consistent with biliary obstruction. Anemia of chronic disease and nutritional anemia were suggested by reduced hematocrit in 34.2%, hemoglobin in 21.95%, and erythrocyte count in 14.6% of cases.

| Table 2: Descriptive statistical analysis of preoperative laboratory parameters | |||||

| Laboratory Finding | Unit | Value* | ↑ rI (%) | ↓ rI (%) | |

| Erithrocytes | x10^12/L | 4.6 (4.22-4.75) | 4.88 | 14.63 | |

| Hemoglobin | g/L | 125.7 ± 17.2 | 0 | 21.95 | |

| Hematocrit | % | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0 | 34.15 | |

| ESR | mm/h | 27 (18-31) | 87.8 | 0 | |

| Leukocytes | x10^9/L | 10 (8.1-11.8) | 43.9 | 0 | |

| Platelets | x10^9/L | 295.8 ± 80.9 | 4.88 | 7.32 | |

| AST | U/L | 41 (25-58) | 63.41 | 0 | |

| ALT | U/L | 42 (33-63) | 78.05 | 4.88 | |

| γGT | U/L | 58 (29-75) | 85.37 | 0 | |

| LDH | U/L | 241 (202-296) | 36.59 | 2.44 | |

| ALP | U/L | 230.6 ± 100 | 31.7 | 2.44 | |

| Bilirubin | Total | µmol/L | 18.6 (12.3-49.8) | 78.05 | 0 |

| Direct | µmol/L | 6.2 (3.7-16.9) | 48.78 | 0 | |

| Indirect | μmol/L | 12.2 (8.8-21.8) | 78.05 | 2.44 | |

| Amylase | U/L | 70 (60-88) | 12.2 | 0 | |

| Lipase | U/L | 35 (45-61) | 63.41 | 0 | |

| CRP | mg/L | 13 (5-30) | 60.98 | 0 | |

| * Values are presented as median (q1-q3) for non-parametric distributions and mean ± sd for normally distributed variables. | |||||

Table 3 displays the deviations in specific preoperative laboratory parameters observed in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of spherocytosis, in comparison to those without the condition. Statistically significant differences were observed only in erythrocyte count after correction for multiple comparisons: decreased erythrocyte counts were present in 57.1% of patients with spherocytosis compared to 5.88% without (p = 0.0045, corrected p = 0.0383). Although hemoglobin and hematocrit differences were initially significant, they lost significance after adjustment (p = 0.174 and p = 0.0646, respectively). In the remaining laboratory findings, deviations were approximately comparable between patients with and without spherocytosis, and any observed differences did not reach statistical significance.

| Table 3: Comparison of preoperative laboratory abnormalities between patients with and without spherocytosis | |||||||||

| Spherocytosis | |||||||||

| Present | Absent | ||||||||

| Abnormality | Laboratory finding | N (n=7) | % | N (n=34) | % | p | Corrected p* | ||

| ↓ | Erythrocytes | 4 | 57.14 | 2 | 5.88 | 0.0045 | 0.0383 | ||

| ↓ | Hemoglobin | 4 | 57.14 | 5 | 14.71 | 0.0307 | 0.174 | ||

| ↓ | Hematocrit | 6 | 85.71 | 8 | 23.53 | 0.0038 | 0.0646 | ||

| ↑ | ESR | 6 | 85.71 | 30 | 88.24 | 0.6581 | 1 | ||

| ↓ | Leukocytes | 3 | 42.86 | 14 | 41.18 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ↓ | Platelets | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8.82 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ↑ | AST | 5 | 71.43 | 21 | 61.76 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ↑ | ALT | 6 | 85.71 | 26 | 76.47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ↑ | γGT | 5 | 71.43 | 30 | 88.24 | 0.2677 | 0.6501 | ||

| ↑ | LDH | 5 | 71.43 | 10 | 29.41 | 0.0787 | 0.2676 | ||

| ↑ | ALP | 1 | 14.29 | 12 | 35.29 | 0.0399 | 0.1696 | ||

| ↑ | Total | Bilirubin | 6 | 85.71 | 26 | 76.47 | 1 | 1 | |

| ↑ | Direct | 4 | 57.14 | 16 | 47.06 | 0.6965 | 1 | ||

| ↑ | Indirect | 6 | 85.71 | 26 | 76.47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ↑ | Amylase | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14.71 | 0.5668 | 0.2525 | ||

| ↑ | Lipase | 2 | 28.57 | 23 | 67.65 | 0.0891 | 1 | ||

| ↑ | CRP | 5 | 71.43 | 20 | 58.82 | 0.6849 | 1 | ||

| *P-value after correction for multiple comparisons using the benjamini-hochberg method (fdr) | |||||||||

Gallstones were confirmed by ultrasound in 39 patients.

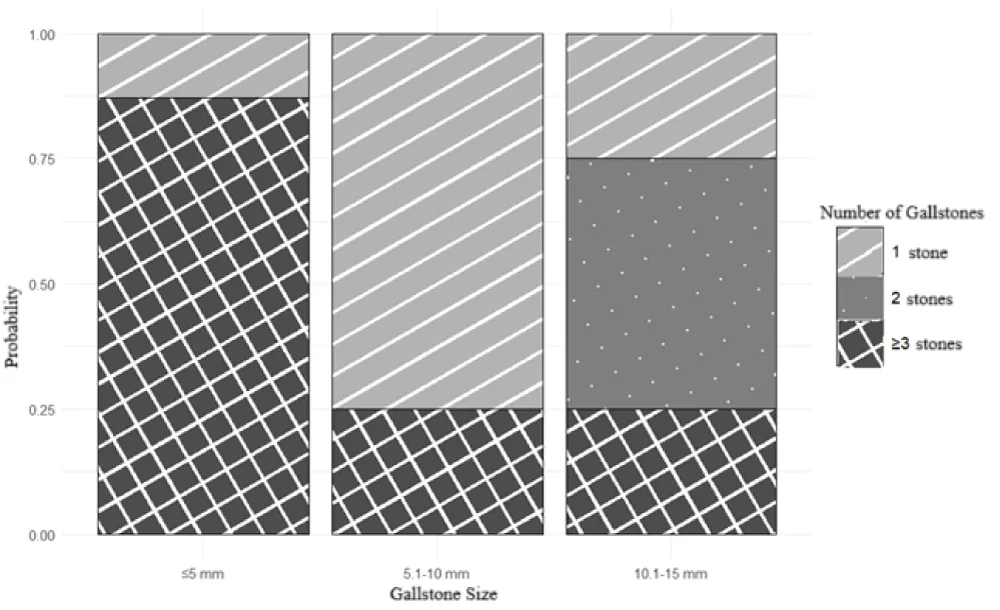

The majority (74.4%) had multiple stones, while 20.5% had a solitary stone (Figure 6). No statistically significant association was found between stone number and age (p = 0.8455) or presence of spherocytosis (p = 0.7529).

Figure 6: Distribution of Gallstone Count Among Patients.

Ultrasound evaluation demonstrated gallbladder wall thickening in 16 patients (39%) and biliary duct dilatation in 8 patients (19.5%).

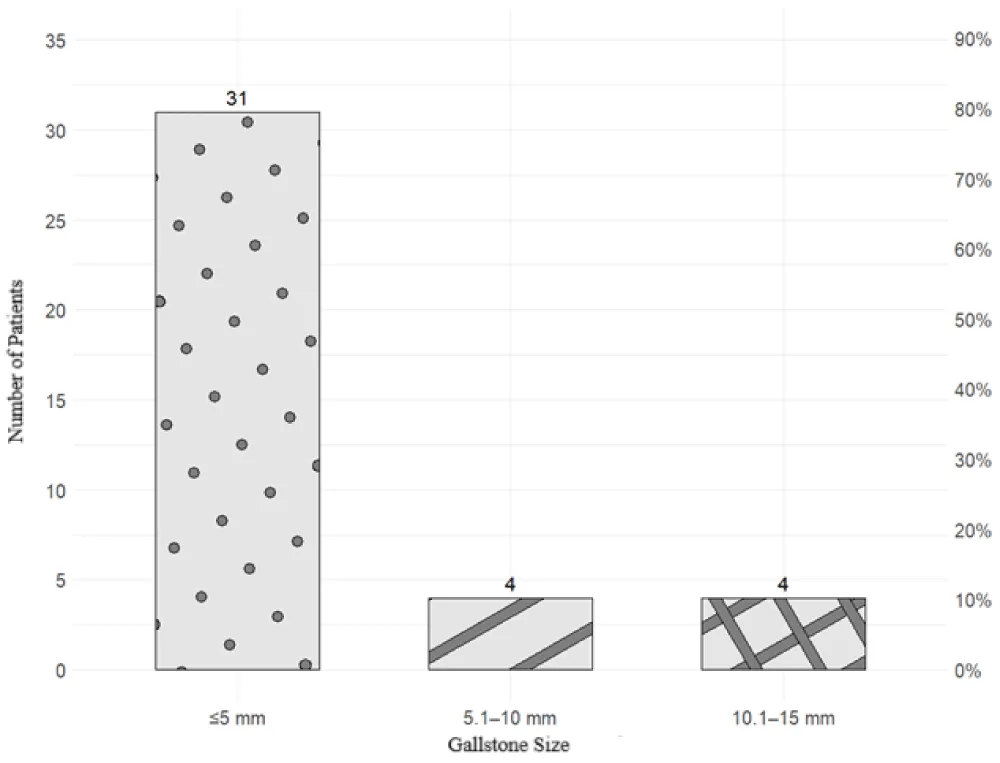

Stone size was ≤5 mm in 79.5% of patients (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Prevalence of Gallstone Size Among Patients.

A significant negative correlation was observed between stone size and number (p = -0.53, p < 0.001), with smaller stones more likely to be multiple (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Predictive Values of Gallstone Count in Relation to Stone Size.

Age was not significantly associated with stone size (p = 0.5775).

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 90.2% of cases. Open cholecystectomy or conversion to open occurred in 4.88% each (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Frequency of Surgical Approaches in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Cholecystectomy.

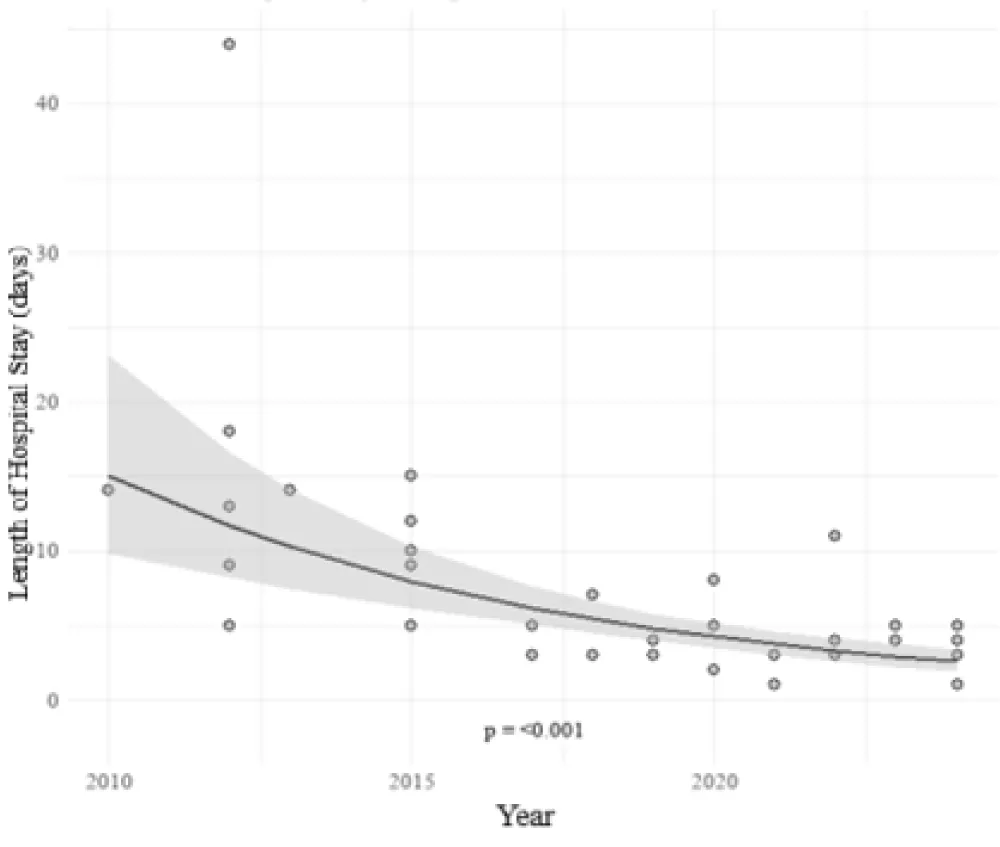

Median hospital stay was 4 days (range: 1–44, IQR = 6), and median drain removal was on postoperative day 2 (range: 1–8, IQR = 2) (Figure 10). Both variables showed non-normal distributions (p < 0.01).

Figure 10: Boxplot Distribution of Postoperative Parameters (Day of Drain Removal and Length of Hospital Stay).

A significant decreasing trend in hospital stay over the study period was observed, with an annual reduction of approximately 11.9% (95% CI: 8.2% to 15.6%, p < 0.01) (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Log-Linear Regression of Hospital Stay Duration Across Surgical Years.

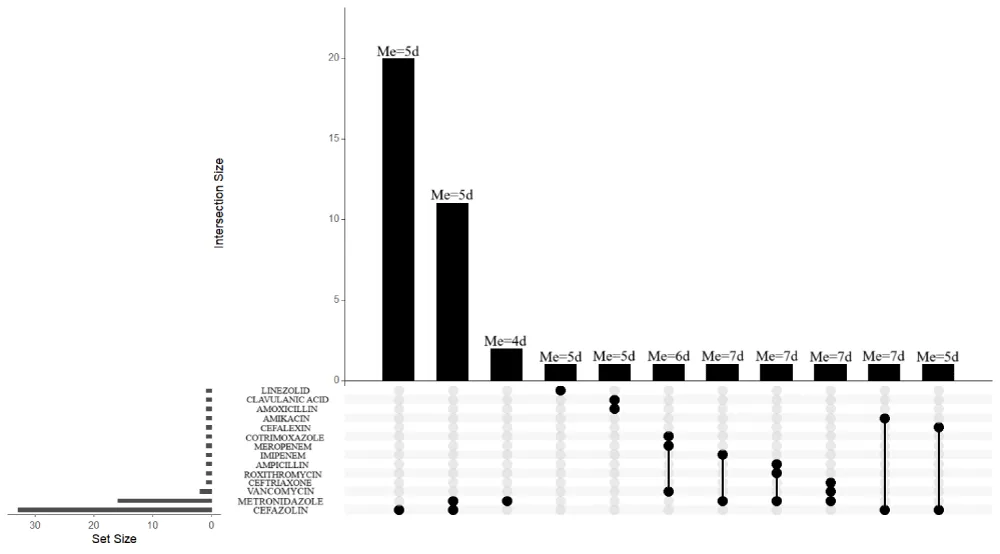

Postoperative antibiotic regimens most commonly included cefazolin (20 patients, 48.8%), followed by a combination of cefazolin and metronidazole (11 patients, 26.8%) (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Expected Duration of Postoperative Antibiotic Therapy by Composition of Antibiotic Regimens.

Histopathology confirmed chronic cholecystitis in 36 patients (87.8%). Findings of gallbladder wall thickening and bile duct dilation correlated with ultrasonographic observations. The only observed anatomic anomaly was a Phrygian cap found in 4 patients (9.76%). Gallbladder polyps were observed in 1 patient (2.44%), as well as a hydropic gallbladder (2.44%). Antral metaplasia was present in 12 patients (29.3%).

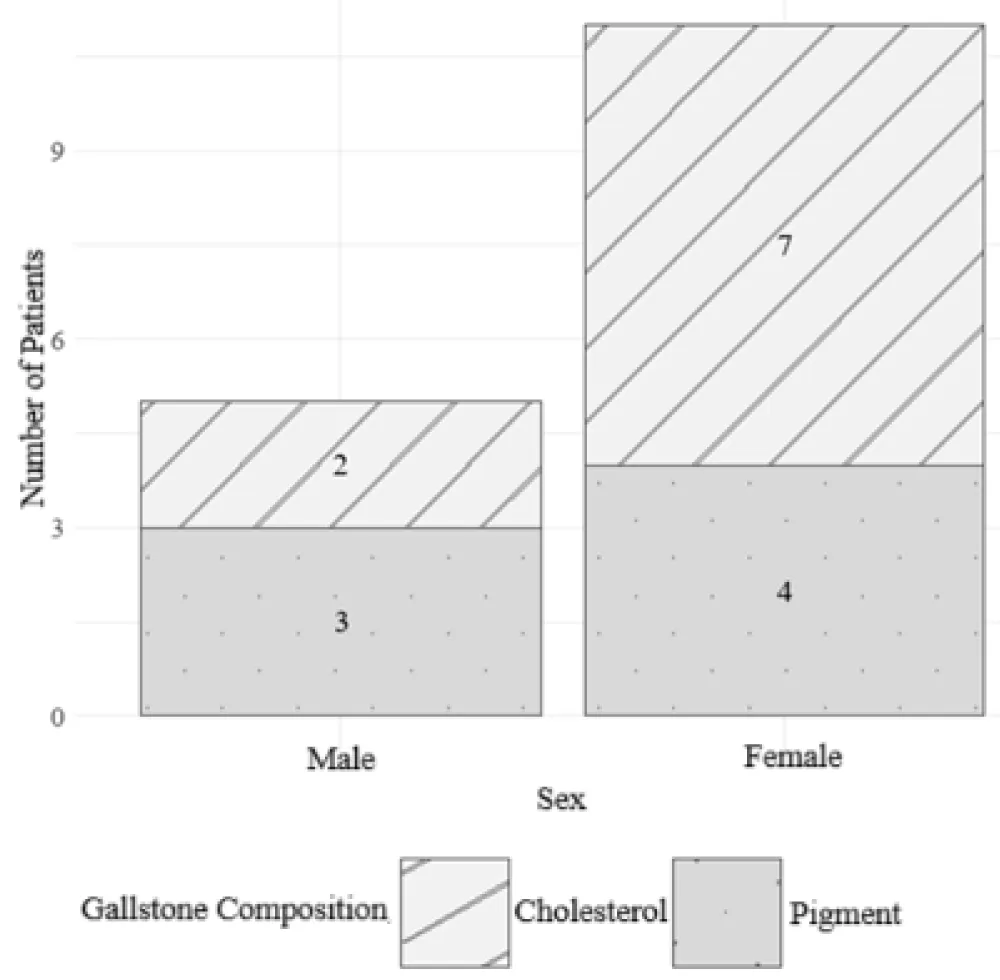

Gallstone composition was documented in 16 patients (41.03%): 9 cholesterol stones (56.25%) and 7 pigment stones (43.75%). All pigment stones were black gallstones, which occurred in patients with hereditary spherocytosis.

Figure 13 illustrates the distribution of pigment and cholesterol gallstones by sex. Cholesterol stones were more frequently observed in female patients, while pigment stones were more common in males; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.5962). The estimated odds ratio was 0.41, indicating that girls had approximately 2.5 times higher odds of developing cholesterol stones compared to boys, although this association was not statistically significant, given the wide 95% confidence interval (0.02 to 5.24), which includes the null value of 1.

Figure 13: Frequency of Pigment and Cholesterol Gallstones by Sex.

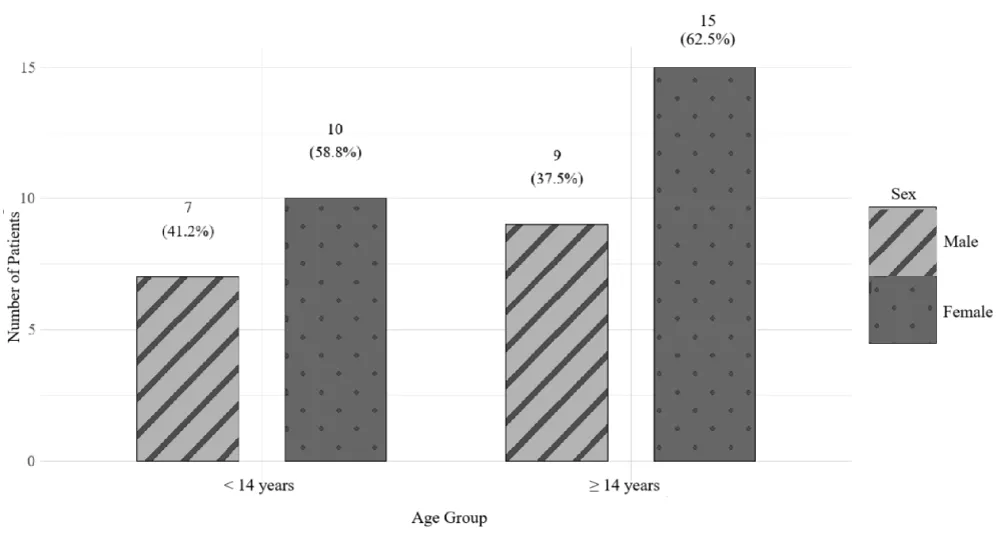

Subsequent analyses examined differences in clinical and laboratory characteristics between two age-defined groups: children younger than 14 years and those aged 14 years or older.

Out of a total of 41 patients, 17 (41.5%) were younger than 14 years, while 24 (58.5%) were 14 years of age or older.

Both age groups included a higher proportion of female patients: 10 girls (58.8%) in the group younger than 14 years and 15 girls (62.5%) in the group aged 14 years or older. Although the older age group had 3.7% more female patients, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 1). Therefore, there is no evidence of a significant difference in sex distribution between the age groups (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Distribution of Patients by Sex Within Two Age Groups (<14 and ≥14 Years).

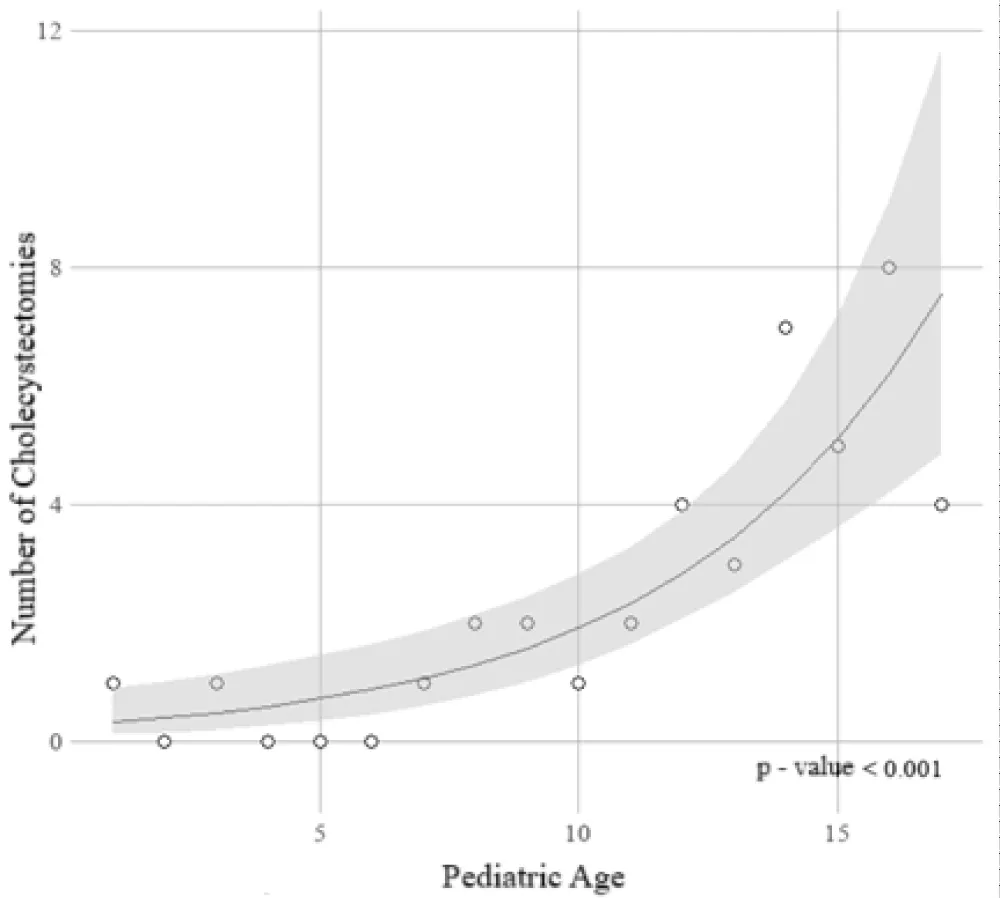

Poisson regression analysis demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the risk of cholecystectomy with advancing age (p < 0.01). The estimated incidence rate ratio (IRR) was 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1 to 1.3), indicating that with each additional year of age, the risk of undergoing cholecystectomy increased by 21.5% (95% CI: 13.9% to 31.6%). These findings are presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15: Trend in the Risk of Cholecystectomy by Pediatric Age – Regression Analysis Results.

The distribution of BMI values in patients under the age of 14 significantly deviated from normality (p = 0.022), whereas in the ≥14 age group, the distribution conformed to a normal distribution (p = 0.6091). Although Z-scores were normally distributed in both groups, their variances were not homogeneous (p = 0.027). In the < 14 age group, the median BMI was 17.8 kg/m² (range: 15–32.8 kg/m²), with a mean Z-score of 0.81 ± 0.97, corresponding approximately to the 79th percentile. In patients aged ≥14 years, the median BMI was 24.7 kg/m² (range: 19.8–32.1 kg/m², IQR: 3.5), and the mean Z-score was 1.09 ± 0.58, corresponding approximately to the 86th percentile. However, comparison of Z-scores between the two groups showed no statistically significant difference (p = 0.3051).

Both cases of acute acalculous cholecystitis were observed in the < 14-year age group. In this younger cohort, the presence of underlying conditions with a potential etiological role in gallbladder disease was identified in 7 patients (41.18%), compared to 3 patients (12.5%) in the ≥14 years age group. Although the calculated odds ratio was 4.7, suggesting that the likelihood of such conditions was nearly five times higher in children under 14, the 95% confidence interval (0.85–34.22) includes the value of 1, and the p-value was 0.063. Therefore, the observed difference did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4 presents the distribution of abnormal laboratory values among patients younger than 14 years (N = 17) and those aged 14 years or older (N = 24). After adjustment, no statistically significant differences were found in laboratory abnormalities between the two groups (p < 0.05), suggesting a similar biological response across age groups. There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of gallstone count between the age groups (p = 0.846). The number of gallstones was comparably distributed among patients younger and older than 14 years.

| Table 4: Comparison of preoperative laboratory abnormalities between patients aged <14 and ≥14 years | ||||||||

| < 14 Years | ≥ 14 Years | |||||||

| Abnormality | Laboratory finding | N (n=17) | % | N (n=24) | % | p | corrected p* | |

| ↓ | Erythrocytes | 5 | 29.41 | 1 | 4.17 | 0.0657 | 0.5585 | |

| ↓ | Hemoglobin | 6 | 35.29 | 3 | 12.5 | 0.128 | 0.7253 | |

| ↓ | Hematocrit | 7 | 41.18 | 7 | 29.17 | 0.5121 | 1 | |

| ↑ | ESR | 15 | 88.24 | 21 | 87.5 | 1 | 1 | |

| ↓ | Leukocytes | 8 | 47.06 | 10 | 41.67 | 0.7589 | 1 | |

| ↓ | Platelets | 2 | 11.76 | 1 | 4.17 | 0.5598 | 1 | |

| ↑ | AST | 12 | 70.59 | 14 | 58.33 | 0.5194 | 1 | |

| ↑ | ALT | 15 | 88.24 | 17 | 70.83 | 0.2623 | 1 | |

| ↑ | γGT | 14 | 82.35 | 21 | 87.5 | 0.6786 | 1 | |

| ↑ | LDH | 8 | 47.06 | 7 | 29.17 | 0.3281 | 1 | |

| ↑ | ALP | 1 | 5.88 | 12 | 50 | 0.0052 | 0.0844 | |

| ↑ | Total | Bilirubin | 12 | 70.59 | 20 | 83.33 | 0.45 | 1 |

| ↑ | Direct | 9 | 52.94 | 11 | 45.83 | 0.7557 | 1 | |

| ↑ | Indirect | 12 | 70.59 | 20 | 83.33 | 0.45 | 1 | |

| ↑ | Amylase | 2 | 11.76 | 3 | 12.5 | 1 | 1 | |

| ↑ | Lipase | 9 | 52.94 | 17 | 70.83 | 0.3281 | 1 | |

| ↑ | CRP | 10 | 58.82 | 15 | 62.5 | 1 | 1 | |

| * P-value after correction for multiple comparisons using the benjamini-hochberg method (fdr) | ||||||||

In the younger age group, the majority of gallstones measured ≤5 mm (73.33%), compared to 83.33% in the older group. Stones measuring 5.1–10 mm were more frequently observed in the younger group (20%) than in the older group (4.17%). However, these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.478).

No statistically significant difference was observed in the length of hospital stay or the day of drain removal between the groups (p = 0.7686 and p = 0.9091, respectively).

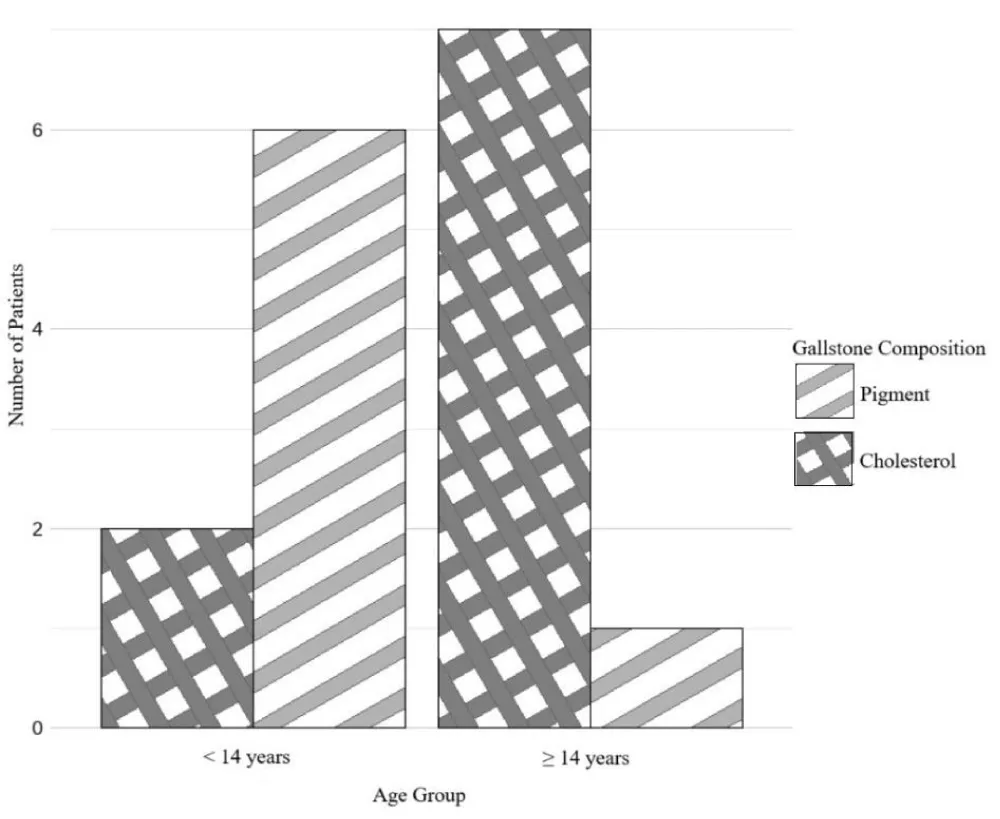

Pigment stones were more common in children under 14 years (75%), while in the older group, pigment stones were present in only 12.5% of patients. In contrast, cholesterol stones were more prevalent among patients older than 14 years, with a frequency of 87.5% compared to 25% in the younger group. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0406) and is illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16: Distribution of Gallstone Composition by Age Group

This retrospective descriptive study investigated the clinical characteristics of pediatric patients who underwent cholecystectomy between 2010 and 2024. The analysis encompassed multiple variables, including trends in the incidence of cholecystectomy, laboratory abnormalities, gallstone count and size, and length of hospitalization. Special emphasis was placed on identifying differences in these characteristics based on the patient's age.

Between 2010 and 2024, the number of cholecystectomies performed showed a statistically significant annual increase of 11.2% (95% CI: 3.1% to 19.9%, p = 0.0057). These findings align with trends reported in other studies examining the incidence of cholecystectomy in the pediatric population. Khoo et al., for example, documented an increase in the incidence of pediatric cholecystectomy in England from 0.78 to 2.78 per 100,000 children between 1997 and 2012 (p < 0.0001). Additionally, a rise in the proportion of female patients (from 69% to 79%, p = 0.02) and white children (from 48% to 77%, p < 0.0001) was observed. The authors described this increase as “epidemic” in nature [6]. These patterns suggest a potential role of geographic and environmental factors in modulating disease incidence. Given the similarities in dietary habits, as well as geographic, demographic, and healthcare-related contexts, studies conducted in neighboring countries may offer more relevant insights for interpreting the incidence of cholecystectomy in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Pogorelić, et al., in a 2019 study from Croatia, reported a marked increase in the number of cholecystectomies between two patient groups stratified by surgical year: from 11 in Group I (1998–2007) to 34 in Group II (2008–2017). A statistically significant decline was also noted in the proportion of patients undergoing cholecystectomy due to hereditary spherocytosis (from 63.6% to 11.8%, p = 0.001) [7]. These findings are consistent with larger cohort studies, such as the one by Murphy, et al., which analyzed 6,040 pediatric cholecystectomy cases over 20 years in New York. The incidence increased from 8.8 to 13.1 per 100,000 children (p < 0.001) [3]. The aforementioned studies largely attribute this rising trend to the increasing prevalence of pediatric and adolescent obesity, now considered the primary driver of the “epidemic” of gallbladder disease in this population. All other indications show a statistically significant decline, while the incidence of cholesterol gallstone disease continues to rise [8]. Supporting this notion, a study by Fradin, et al. published in 2013 demonstrated a direct correlation between pediatric obesity and hospitalization rates for cholelithiasis (r = 0.87, p = 0.0025). Each one-unit increase in BMI Z-score was associated with a 79% higher risk of developing cholelithiasis (p < 0.0001) [9]. Although the burden of gallbladder disease in the pediatric population is undoubtedly increasing, the overall prevalence remains relatively low. The present study was conducted at a single tertiary care center in Sarajevo, with a relatively small sample size, thereby limiting the external validity of the findings. A more comprehensive assessment of the nationwide trend in pediatric cholecystectomy incidence in Bosnia and Herzegovina would require multicenter or population-based studies. Despite these limitations, overweight or obesity was documented in 56.1% of patients in our cohort—a finding that warrants further investigation into the etiological factors contributing to pediatric cholelithiasis.

Hereditary spherocytosis was identified in 7 pediatric patients (17.07%) in this study, while 34 patients (82.93%) had no evidence of a hemolytic disorder. The majority of patients diagnosed with spherocytosis belonged to the age group younger than 14 years. The presence or absence of a hemolytic disorder was used to stratify patients into two groups: those with a confirmed diagnosis of spherocytosis and those without hematological abnormalities. Differences were analyzed across preoperative laboratory parameters commonly assessed in pediatric gallbladder disease, including red blood cell count, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, leukocyte and platelet counts, AST, ALT, γGT, LDH, ALP, total, direct, and indirect bilirubin, amylase, lipase, and CRP. Following adjustment for multiple comparisons, a statistically significant difference was observed only in red blood cell (RBC) count. Decreased RBC values were documented in 57.44% of patients with spherocytosis compared to 5.88% of patients without (p = 0.0383), consistent with the hemolytic nature of the disease. Although hemoglobin and hematocrit levels initially showed statistical significance (p = 0.0307 and p = 0.0038, respectively), significance was not retained after correction (p=0.174 and p = 0.0646, respectively), and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Hemoglobin levels were decreased in 57.14% of patients with spherocytosis versus 14.71% without, while reduced hematocrit was observed in 85.71% compared to 23.53%, respectively. These differences, however, did not reach statistical significance. For the remaining laboratory markers, abnormalities were similarly distributed across both groups. In a 2021 study, Çelik et al. analyzed laboratory profiles of 67 pediatric patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Clinical manifestations included jaundice (64.2%), fatigue (26.9%), and syncope (7.5%). Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly in 65.6% and splenomegaly in 77.6% of patients. Mean hemoglobin concentration was 80.3 ± 20.1 g/L (range 50.1–150.3 g/L), and the average level of indirect bilirubin was 59.9 ± 68.4 μmol/L. Splenectomy with simultaneous cholecystectomy due to ultrasound-confirmed cholelithiasis was performed in 41% of cases. Postoperative outcomes included a statistically significant increase in hemoglobin (p < 0.01) and a marked decrease in indirect bilirubin levels (p < 0.01) [10]. To date, no studies have directly compared laboratory findings between pediatric patients with gallbladder disease with and without spherocytosis. Based on the results of the present study, standard laboratory parameters appear to lack the sensitivity and specificity needed to detect hereditary spherocytosis as an underlying cause of cholelithiasis in patients without a prior hematologic diagnosis. Observed differences in RBC count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and sedimentation rate are not sufficient to establish the diagnosis and should prompt further clinical and laboratory evaluation. According to updated diagnostic protocols for hereditary spherocytosis proposed by Wu, et al. in 2021, evaluation should include assessment of MCV, MCH, and MCHC, as well as a peripheral blood smear for all patients presenting with signs and symptoms of anemia, jaundice, or splenomegaly. A presumptive diagnosis may be made in patients with low values of the aforementioned parameters and increased numbers of spherocytes on peripheral smear. Confirmation requires demonstration of hemolysis through hemoglobin and reticulocyte levels, blood smear morphology, and total and unconjugated bilirubin concentrations. Family history should be thoroughly evaluated, and in diagnostically challenging cases, genetic testing and screening assays may be indicated, including osmotic fragility testing, eosin-5-maleimide binding test, acidified glycerol lysis test, Coombs test, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity assay [11]. In conclusion, gallbladder disease due to hereditary spherocytosis or other hemolytic conditions shares a largely overlapping routine laboratory profile with primary biliary pathology, necessitating a more detailed diagnostic workup to determine etiology.

Based on ultrasonographic and histopathological diagnostics, the number and size of gallstones were analyzed in 39 patients from this study with confirmed cholelithiasis. The majority of patients (n = 29; 74.36%) had multiple gallstones. There was no statistically significant difference in stone count between patients with hereditary spherocytosis and those without a hemolytic disorder (p = 0.7529). Similarly, no significant association was observed between patient age and gallstone number (p = 0.8455). Although the odds ratio was below 1 (OR=0.9), suggesting a potential decrease in the likelihood of having multiple stones with increasing age, the confidence interval was wide (95% CI: 0.75–1.22) and included the null value, indicating insufficient evidence to support a correlation between age and stone number in this cohort. The majority of sonographically detected gallstones (79.49%) measured less than 5 mm in diameter. A strong negative correlation was observed between stone size and number (p = –0.53, p < 0.001), indicating that smaller stones tend to occur in greater numbers. Stones measuring ≤5 mm were most frequently found in multiples (≥3), whereas larger stones were more commonly solitary. Among children under the age of 14, 73.33% had gallstones measuring ≤5 mm, compared to 83.33% in the older age group. Stones measuring 5.1–10 mm were more frequently observed in the younger cohort (20%) compared to older patients (4.17%); however, these differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.478). These findings are consistent with other studies reporting small and multiple gallstones in the majority of pediatric patients. In a 2020 study from South Korea, Lee et al. evaluated the clinical characteristics and therapeutic modalities of cholelithiasis in 65 pediatric patients. Multiple stones were identified in 31 patients (47.7%), while solitary or dual stones were less common. Gallstones < 5 mm were detected in 45 patients (69.2%), and were visualized by plain abdominal radiography in 7 cases (11%) [12]. No prior studies specifically examining the relationship between the number and size of gallstones in children were identified, although clinical assumptions align with the findings of the present study. Conversely, the hypothesis that microlithiasis is associated with a higher rate of complications remains unproven in pediatric populations. In 2016, Tuna Kirsaclıoğlu et al. conducted a study in Turkey evaluating clinical presentation, risk factors, complications, treatment, and outcomes in 254 pediatric patients who underwent cholecystectomy. No statistically significant association was found between stone size and symptoms, etiologic factors, or complications [13]. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis, smaller and solitary stones have been shown to have a higher likelihood of spontaneous resolution and favorable response to conservative therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid. A study published by Serdaroğlu, et al. in 2016 examined the demographic and clinical characteristics of 70 pediatric patients with cholelithiasis. The likelihood of gallstone dissolution was 3.6 times higher in patients with stones < 5 mm (OR = 3.65, p = 0.02), 3.9 times higher in children under 2 years of age (OR = 3.92, p = 0.021), and 13.9 times higher in patients with solitary stones (OR = 13.97, p = 0.003) [14]. Further large-scale prospective studies are warranted to determine the potential influence of age and sex on gallstone number and size in pediatric populations.

The median length of hospital stay in this study was 4 days. Over the years, the duration of hospitalization has decreased by approximately 11.9% annually (95% CI: 8.2% to 15.6%, p < 0.01). These findings are consistent with those reported in other recent studies. Langballe, et al. conducted a study in Denmark between 2006 and 2010 on a cohort of 35,444 cholecystectomized patients, where 91% were discharged within 3 days postoperatively without subsequent readmission. No 30-day postoperative mortality was recorded [15]. In 2013, Mattson et al. published a study involving 76,524 pediatric patients who underwent cholecystectomy, reporting a median hospital stay of 2 days [16]. In both aforementioned studies, as well as in the present one, the majority of patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, while conversion to open surgery or primary open cholecystectomy was reported in only a small number of cases. The outcomes of open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pediatric patients were compared in a systematic review and meta-analysis by Steffens et al. in 2020, which included 21 studies and a pooled sample of 927 children and adolescents. Patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy experienced fewer postoperative complications (RR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.35 to 0.94) and had a reduced hospital stay by an average of 4 days compared to those who underwent open surgery (MD: −3.73; 95% CI: −4.88 to −2.59). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered a safe operative approach for treating symptomatic gallbladder disease in children and adolescents, with no reported postoperative mortality and acceptable rates of conversion and postoperative complications [17]. Therefore, the results of this study are comparable to global benchmarks in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and indicate that Bosnia and Herzegovina is aligned with international practices in pediatric minimally invasive surgery. This approach promotes faster recovery and return to normal daily activities in pediatric patients. Consequently, it also contributes to a reduction in postoperative complications and associated costs of their management and prolonged inpatient care. Nevertheless, the encouraging data regarding shortened hospital stay should be interpreted with caution, particularly in light of outlier cases involving patients with comorbidities that complicate the surgical procedure and recovery. This is evidenced by the wide range of hospitalization durations observed in this study, spanning from 1 to 44 days. Although robot-assisted surgery was initially expected to revolutionize the management and postoperative course of gallbladder disease, currently available evidence has not confirmed this assumption. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Singh et al. in 2024 compared laparoscopic and robot-assisted cholecystectomy in pediatric patients, including six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and a total of 1,013 cholecystectomized individuals. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was significantly shorter in duration (MD: −10.23; 95% CI: −16.23 to −4.22, p=0.0008), with no statistically significant differences in the incidence of bile leakage or postoperative complications (p > 0.05). Additionally, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was significantly more cost-effective (SMD: −7.42; 95% CI: −13.10 to −1.74, p = 0.01) [18]. While there remains room for future high-quality randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses evaluating the efficacy of robot-assisted surgery, conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy currently represents the recommended standard of care for gallbladder disease in the pediatric population.

The results of this study demonstrated that the risk of cholecystectomy significantly increases with age (p < 0.01). The estimated incidence rate ratio (IRR) was 1.215 (95% CI: 1.14 to 1.32), indicating that with each additional year of age, the risk of undergoing cholecystectomy increased by 21.5% (95% CI: 13.9% to 31.6%). A study by Mehta et al., conducted between 2005 and 2008 on a cohort of 404 pediatric patients, reported similar findings. Logistic regression identified Hispanic ethnicity and older pediatric age as independent risk factors for non-hemolytic cholecystectomy (p = 0.019) [19]. A more recent study by Losa et al., conducted between 2014 and 2021 on 64 participants, stratified patients into two age-based groups: Group A (<10 years) and Group B (>10 years). Logistic regression analysis revealed that patients who underwent cholecystectomy were 6.4 times more likely to be older than 10 years (OR = 6.440, p = 0.005). Additionally, this study reported that spontaneous resolution of cholelithiasis was more frequent in children under the age of 2, while complications were more prevalent in the >10 age group [20]. No studies with opposing findings were identified. A retrospective study by Han et al., published in 2016, included 47 patients stratified into two cohorts based on year of surgery: the early group (1999–2006) and the late group (2007–2014). The average age in the early group was 5.94 ± 5.57 years, compared to 10.51 ± 5.57 years in the late group, a statistically significant difference (p = 0.01) [21]. These findings illustrate a notable shift in the pediatric age at which cholecystectomy is indicated, both historically and in contemporary practice. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, particularly considering the overall increase in the incidence of cholecystectomy over time. The number of surgeries in younger children has remained relatively constant and is generally associated with hemolytic etiologies, the incidence of which is stable [1]. Therefore, gallbladder disease should not be overlooked in this younger pediatric age group. Conversely, recent studies report a marked rise in the number of cholecystectomies among older children and adolescents, primarily due to non-hemolytic causes. The increased risk of cholecystectomy with advancing pediatric age is most likely attributable to pubertal hormonal changes, obesity, and insulin resistance. Furthermore, forming definitive conclusions is limited by the complex pathology of chronic cholecystitis, which often results from recurrent, subclinical episodes of gallbladder inflammation that are not treated surgically during the initial attack. Additionally, the formation of gallstones is a complex, long-term process that may only manifest with characteristic symptoms after months or years of disease activity. The true age of onset is often obscured, masked by the age at which surgical intervention occurs. To accurately determine the age at which the risk for non-hemolytic indications for cholecystectomy begins to rise, additional predominantly prospective studies are needed to evaluate the role of hormonal factors, dietary habits, physical activity, and genetic predisposition. Based on current evidence, gallbladder disease should be duly considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older children and adolescents.

In this study, the type of gallstones was documented in the histopathological reports of 16 patients (41.03%). Among these, 9 were cholesterol stones (56.25%), and 7 were pigment stones (43.75%). All pigment stones occurred in children diagnosed with spherocytosis. Cholesterol stones were more frequently observed in female patients, while pigment stones were more common in male patients; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.5962). Among children under the age of 14, pigment stones were considerably more prevalent (75%), whereas cholesterol stones were more frequent in those aged 14 years and older, with a prevalence of 87.5%. This age-based difference reached borderline statistical significance (p = 0.0406). The number of studies analyzing the association between age, sex, and the type of gallstones in pediatric populations is very limited. In 2010, Koivusalo et al. published a study involving 21 cholecystectomized pediatric patients. The authors identified their characteristics and compared them to a cohort of adult patients. Over 70% of patients with confirmed cholesterol stones were female. A positive correlation was observed between body mass index and older pediatric age with the presence of cholesterol stones (r = 0.7, p < 0.05). The authors concluded that cholelithiasis in older girls resembles the typical profile of gallstone disease observed in adults [22]. In the present study, the type of stone was identified in only 16 patients diagnosed with cholelithiasis (41.03%), which represents a significant limitation in data interpretation. Although the observed differences in the prevalence of cholesterol stones between male and female patients did not reach statistical significance, they were notable. It is anticipated that a larger sample size could yield statistically significant results. On the other hand, age stratification (< 14 years vs. ≥1 4 years) showed a borderline statistically significant association, with pigment stones more prevalent in younger children and cholesterol stones more frequent in older children. These findings align with known pathophysiological patterns of cholelithiasis in the pediatric population, where younger children are typically affected by hemolytic disorders, while older children are more likely to develop gallstones due to metabolic factors such as insulin resistance and obesity. In this study, patients were stratified based on the median age of 14 years. However, the hormonal changes of puberty vary significantly between sexes and individuals, making it challenging to determine the exact age at which the distribution of gallstone types begins to diverge. Furthermore, the presence of mixed or brown stones was not documented, which necessitates caution when interpreting these findings.

This study has several important limitations that constrain the interpretation of its findings. The retrospective design carries the inherent risk of incomplete or selectively documented data in the medical records. Furthermore, the study was conducted in a single hospital center and involved a relatively small sample size, which limits the ability to detect potential differences in symptomatology, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and surgical treatment of patients. This also restricts the generalizability of the findings to national, regional, or global pediatric populations. Although stratification based on age and the presence of spherocytosis as an etiological factor for cholelithiasis was attempted, the small size of the subgroups prevented the derivation of statistically robust conclusions. Additionally, changes in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches throughout the study period (2010–2024) may have introduced further variability.

Nevertheless, the findings of this study represent a valuable contribution to the understanding of clinical characteristics in pediatric patients with gallbladder disease and may serve as a foundation for future research in this field. Statistically significant results, as well as observed trends that did not reach the threshold of significance, offer an opportunity for designing prospective studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods. Hematologic disorders and age-based subgroups warrant targeted investigation of relevant laboratory and clinical parameters. Insights from this study could support the standardization of recognition and management strategies for pediatric patients with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis.

The frequency of cholecystectomies in children has increased over the past 15 years.

Overweight and hereditary spherocytosis are significant etiological factors in pediatric cholelithiasis.

Standard laboratory parameters used to evaluate patients with gallbladder diseases are not sufficient to differentiate patients with or without spherocytosis.

A complete clinical and ultrasound examination, as well as sensitive and specific laboratory and screening tests, are required for the diagnosis of pediatric cholelithiasis.

Pediatric patients with verified cholelithiasis more often have multiple microcholeliths < 5 mm.

Pigmentary calculosis is more common in pediatric patients up to 14 years of age, while cholesterol cholelithiasis is more often present in pediatric patients older than 14 years.

- Webmed – Colelithiasis. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/gallstones

- Bogue CO, Murphy AJ, Gerstle JT, Moineddin R, Daneman A. Risk factors, complications, and outcomes of gallstones in children: a single–center review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:303-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0b013e3181b99c72

- Gokce S, Yıldırım M, Erdoğan D. A retrospective review of children with gallstones:single-center experience from Central Anatolia. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:46-53. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2014.3907

- Džiho N, Karavdić K. Pediatric Cholelithiasis Single Center Experience Results of the Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, kcu Sarajevo in the Period 2010-2022. Journal of Clinical Surgery and Research. 4(3);(2023). Available from: https://doi.org/10.31579/2768-2757/081

- Karavdić K. The Specific features of pediatric cholelithiasis.A Literature review. South-East European Endo-Surgery. South-East European Endo-Surgery. 2022;1:50-69. Available from: https://doi.org/10.55791/2831-0098.1.2.207

- Khoo AK, Cartwright R, Berry S, Davenport M. Cholecystectomy in English children: evidence of an epidemic (1997-2012). J Pediatr Surg. February 2014;49(2):284–8; discussion 288. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.11.053

- Pogorelić Z, Aralica M, Jukić M, Žitko V, Despot R, Jurić I. Gallbladder Disease in Children: A 20-year Single-center Experience. Indian Pediatr. 15 May 2019;56(5):384–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30898989/

- Murphy PB, Vogt KN, Winick-Ng J, McClure JA, Welk B, Jones SA. The increasing incidence of gallbladder disease in children: A 20-year perspective. J Pediatr Surg. May 2016;51(5):748–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.02.017

- Fradin K, Racine AD, Belamarich PF. Obesity and symptomatic cholelithiasis in childhood: epidemiologic and case-control evidence for a strong relation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. January 2014. 58(1):102–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0b013e3182a939cf

- Çelik SŞ, Yıldırmak ZY, Genç DB. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of our patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 01 November 2021;43:S22–3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.htct.2021.10.986

- Wu Y, Liao L, Lin F. The diagnostic protocol for hereditary spherocytosis‐2021 update. J Clin Lab Anal. 24 October 2021;35(12):e24034. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.24034

- Lee YJ, Park YS, Park JH. Cholecystectomy is Feasible in Children with Small-Sized or Large Numbers of Gallstones and in Those with Persistent Symptoms Despite Medical Treatment. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 01 September 2020;23(5):430–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2020.23.5.430

- Tuna Kirsaclioglu C, Çuhacı Çakır B, Bayram G, Akbıyık F, Işık P, Tunç B. Risk factors, complications, and outcome of cholelithiasis in children: A retrospective, single-centre review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2016.;52(10):944–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13235

- Serdaroglu F, Koca YS, Saltik F, Koca T, Dereci S, Akcam M, et al. Gallstones in childhood: etiology, clinical features, and prognosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. December 2016;28(12):1468–72. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/meg.0000000000000726

- Langballe KO, Bardram L. Cholecystectomy in Danish children--a nationwide study. J Pediatr Surg. April 2014;49(4):626–30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.12.019

- Mattson A, Sinha A, Njere I, Borkar N, Sinha CK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel. June 2023;21(3):e133–41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2022.09.003

- Steffens D, Wales K, Toms C, Yeo D, Sandroussi C, Jiwane A. What surgical approach would provide better outcomes in children and adolescents undergoing cholecystectomy? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pediatr Surg. 30 September 2020;16(1):24. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-020-00032-0

- Singh A, Kaur M, Swaminathan C, Siby J, Singh KK, Sajid MS. Laparoscopic versus robotic cholecystectomy: a systematic review with meta-analysis to differentiate between postoperative outcomes and cost-effectiveness. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024.;9:3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21037/tgh-23-56

- Mehta S, Lopez ME, Chumpitazi BP, Mazziotti MV, Brandt ML, Fishman DS. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Symptomatic Pediatric Gallbladder Disease. Pediatrics. 01 January 2012;129(1):e82–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0579

- Losa A, Silva G, Mosca S, Bonet B, Moreira Silva H, Santos Silva E. Pediatric gallstone disease-Management difficulties in clinical practice. Gastroenterol Hepatol. February 2025.;48(2):502228. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2024.502228

- Han W, Oh C, Youn JK, Han JW, Byeon J, Kim S et al. Trend of Pediatric Cholecystectomy: Clinical Characteristics and Indications for Cholecystectomy. J Korean Assoc Pediatr Surg. 22 December 2016;22(2):42–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.13029/jkaps.2016.22.2.42

- Koivusalo AI, Pakarinen MP, Sittiwet C, Gylling H, Miettinen TA, Miettinen TE, et al. Cholesterol, non-cholesterol sterols and bile acids in paediatric gallstones. Dig Liver Dis Off J Ital Soc Gastroenterol Ital Assoc Study Liver. January 2010;42(1):61–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2009.06.006